One popular Christmas carol, especially among American Christians, is ‘Angels we have heard on high.’ Its first verse reads,

Angels we have heard on high

Sweetly singing o’er the plains

And the mountains in reply

Echoing their joyous strains

Gloria in excelsis Deo!

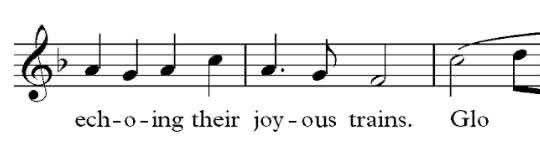

Unfortunately, one source of the music misprinted ‘Echoing their joyous strains’ as ‘Echoing their joyous trains.’

I don’t suppose anyone who commutes would readily think of ‘joyous trains.’ I know my wife didn’t on Thursday evening when her train from Waterloo didn’t initially have a driver, when the passengers were told to disembark to find another train, only then to be told to stay on board. They left twenty-seven minutes late. Joyous trains, indeed.

But if the trains were transformed, that truly would be reason for joy.

The theme this week is ‘Joy’ but it is connected with transformation. So maybe a better title might be, ‘Joy in Transformation.’ These verses in Isaiah give five examples of the transformation the coming Messiah will bring, which lead to joy. It was something the southern kingdom of Judah needed to hear, nervous as the nation was due to the military power of Assyria, which had already conquered the northern kingdom of Israel.

But as so often in Isaiah, we shall see that no earthly king could completely fulfil the prophecy. Even with Jesus, the true Messiah, he would begin the transformational work prophesied, but it will only come to complete fruition with his return in glory.

However, in the meantime, in our in-between time, these point to our work for God’s kingdom today. There are five arenas for joy in the reading; I shall deal with each one briefly.

Firstly, joy for the desert:

The desert and the parched land will be glad;

the wilderness will rejoice and blossom.

Like the crocus, 2 it will burst into bloom;

it will rejoice greatly and shout for joy.

The glory of Lebanon will be given to it,

the splendour of Carmel and Sharon;

they will see the glory of the Lord,

the splendour of our God.

In the Middle East, the people know all about parched deserts in the heat. But God will restore life to the desert as he breaks the drought and beautiful plants bloom and flourish there.

Our droughts today are often caused by our failure as the human race to fulfil the command we were given when God created us: namely to rule over the created order wisely on his behalf. Instead of caring for it, we have exploited it. Now we pay the consequences – but worse, it is the poorer nations who are suffering first and most.

As Christians, we have common cause with those who are concerned for our environment. But we have a unique reason for being involved. It is that we are doing so as stewards of God’s creation, and as a prophetic sign that God will make all things new in his creation. We agree that the world is in a mess, but we engage out of a spirit of hope, not panic.

So let us engage in our creation care as an act of worship and of witness to the Messiah who will renew the earth. And if we listen carefully, we may catch the sound of the world rejoicing, too.

Secondly, joy for the fearful:

3 Strengthen the feeble hands,

steady the knees that give way;

4 say to those with fearful hearts,

‘Be strong, do not fear;

your God will come,

he will come with vengeance;

with divine retribution

he will come to save you.’

At the time of the prophecy, Israel could well have been afraid of Assyria. But as we know, fear comes in many flavours. Fear of war. Fear of death. Fear of other people’s expectations. Fear of losing someone. The list of fears is long.

In the specific context, Isaiah promises that those who are afraid of wrongdoers can take heart, because God will judge the wicked who are scaring them.

And yet there is still a universal application. It is often said – and I confess I have not checked the veracity of this – that the words, ‘Do not be afraid’ occur three hundred and sixty-five times in the Bible. One for every day of the year. You can have one day of fear in a leap year!

God does not want us paralysed by fear. He wants us animated by love. And so, he promises to banish the forces and the people that cause us to fear. The life of the messianic age to come will not be characterised by fear. It will be an eternal age of love.

And if God promises that for us, we can ask ourselves, what can we do to help remove fear from the lives of other people? Sometimes we can banish the cause of fear. In other circumstances, we may not be able to do that, but we may be able to show how to live without fear when unwelcome things happen.

I know how easy it is to panic. My body goes into panic mode before my mind catches up with the truth. For me, God’s message of peace and love comes through human beings, not least my wife. There has been more than one occasion when people who didn’t like me in churches have made up false and malicious Safeguarding accusations against me. One time, my Superintendent phoned me and said, ‘Watch your back on Sunday morning.’ Debbie has helped me be anchored in truth when lies have flown about.

Thirdly, joy for the silenced:

5 Then will the eyes of the blind be opened

and the ears of the deaf unstopped.

6 Then will the lame leap like a deer,

and the mute tongue shout for joy.

There is more than one way of reading these words. Some take them literally as a promise of healing, and we saw in our Gospel reading from Matthew: Jesus did heal the blind, the deaf, and the lame. I wouldn’t want to deny that, nor the promise of full healing when Jesus comes again and makes all things new. I would encourage us to pray for the sick, just so long as we don’t treat chronically ill or disabled people purely as prayer projects rather than people with dignity. As the title of one book puts it, My Body Is Not A Prayer Request.

But I will say there is a wider meaning to these words. Why did I introduce this point as ‘joy for the silenced’? For this reason. Our English translations say at the end of the quote, ‘the mute tongue [will] shout for joy.’ But the words ‘for joy’ are not there in the Hebrew. The mute will shout. That’s it. People who have been silenced by those who oppress them find their voice in the kingdom of God. The persecuted are vindicated and set free. The people that society does not value are of great worth and significance to Jesus.

The early church did this by the way they gave importance to slaves and women. Jesus calls us too to value those who would not be elevated by our society. He longs for them to find their place in his family and his kingdom purposes. Let’s not evaluate people by worldly standards, but by the fact that they are loved and cherished by God in Jesus.

Fourthly, more joy for the desert:

Water will gush forth in the wilderness

and streams in the desert.

7 The burning sand will become a pool,

the thirsty ground bubbling springs.

In the haunts where jackals once lay,

grass and reeds and papyrus will grow.

We’re back in the wilderness, but to make a different point. This time, we see the conditions coming together so that life can flourish. Water to drink. Papyrus to make documents. Reeds to make household items.

In this context, artisans, craftsmen, and business can flourish. Their raw materials are plentiful again.

And so, I want to suggest to you that one way we can be a sign of the Messiah’s coming kingdom is by supporting human flourishing, including our local businesses.

Is that a Christian thing to do? I think so. Remember how later the people of Judah were taken into exile in Babylon. The prophet Jeremiah wrote a letter to the exiles. You can find it in Jeremiah 29. In that letter, he tells these Jews who have been separated from their own land and temple that were so vital to their understanding of salvation that they were to seek the prosperity of the city to which they had been taken. Yes – even a pagan city. Go and bless the pagans, says Jeremiah: it is a sign of God’s covenant love.

Let’s cultivate our relationships with local shops and businesses. Not only by giving them our custom, but that when we do so we take an interest in them and we build relationships with them. I have known ecumenical groups of churches in a village take boxes of chocolates to every business in that village at Christmas, with a card thanking them for all they do, and offering to pray for them if they would like it.

Which shops, businesses, or community groups do you appreciate here? Can you bless them? I’m sure you can. Maybe it will provoke questions.

Fifthly and finally, joy for the temple:

8 And a highway will be there;

it will be called the Way of Holiness;

it will be for those who walk on that Way.

The unclean will not journey on it;

wicked fools will not go about on it.

9 No lion will be there,

nor any ravenous beast;

they will not be found there.

But only the redeemed will walk there,

10 and those the Lord has rescued will return.

They will enter Zion with singing;

everlasting joy will crown their heads.

Gladness and joy will overtake them,

and sorrow and sighing will flee away.

The highway of holiness, on which only the redeemed and not the unclean may walk, is surely the road to the temple in Jerusalem.

This reminds us that when Jesus is present among his people, there is joy. Yes, of course we will be reverent: I am not calling for some religious chumminess with God. But for all that, to have the Messiah in our midst will be a cause for joy and it will reflect in the way we are together in worship and in the sharing of our lives together. With Jesus, church is to be a place of joy.

Today, we only have that experience of Jesus by the presence of his Spirit within us and in our midst. But part of the fruit of the Spirit is joy! And one day, we shall all be together in the presence of Jesus and his Father, too.

It’s nice that we look forward to seeing our friends at church. But that doesn’t make us any different from anyone else. Do we have a sense of joy that Jesus will be present with us, and indeed that we are each bringing him with us to our gathering? That is what the messianic community is like.

Conclusion

Joy to the world, we sing at this time of year, the Lord is come. And when the Lord comes, there is joy. Joy for the broken, joy for God’s people and joy for all creation.

And when he comes again, the joy will be magnified and sorrow banished.

Let us, the followers of Jesus, then, also be joy-bringers.