This is a very lightly revised version of my old sermon Jesus Of The Transfiguration.

Advent, The Prologue and Relationships: 4 Jesus and Moses (John 1:1-18)

Moses isn’t the first Old Testament character that comes to our mind at Christmas, I’ll give you that. Maybe we think of Isaiah prophesying the virgin birth or the One who is called Wonderful Counsellor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, and Prince of Peace. We might remember Micah and his prophecy that the Messiah would be born in Bethlehem, which Herod’s advisers quote when the Magi show up.

But Moses?

Well, John seems to think it’s worth contrasting Jesus with Moses at the end of our great passage. Hear verses 14 to 18 again:

14 The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us. We have seen his glory, the glory of the one and only Son, who came from the Father, full of grace and truth.

15 (John testified concerning him. He cried out, saying, ‘This is the one I spoke about when I said, “He who comes after me has surpassed me because he was before me.”’) 16 Out of his fullness we have all received grace in place of grace already given. 17 For the law was given through Moses; grace and truth came through Jesus Christ. 18 No one has ever seen God, but the one and only Son, who is himself God and is in the closest relationship with the Father, has made him known.

Why didn’t I just read verse 17, which is the only verse here that explicitly mentions Moses? Because even when he’s not named, John is alluding to him. And by doing so, John tells us more about what the Good News of Jesus is.

I’m going back to three episodes in Moses’ life that John has in mind and we’ll see how the comparison and contrast with Jesus tells us about the wonder of the Incarnation.

Firstly, we go to the wilderness:

14 The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us. We have seen his glory, the glory of the one and only Son, who came from the Father, full of grace and truth.

When we read, ‘The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us,’ the English ‘made his dwelling’ if translated more literally would be ‘tabernacled’ Jesus tabernacled among us. Why is that significant?

Do you remember the tabernacle that Moses was instructed to get Israel to construct? It was the dwelling-place of God’s presence that the Israelites carried with them in the wilderness. And indeed it remained so until the Temple was built, centuries later, in Jerusalem.

The tabernacle was the portable presence of God. When John says that Jesus tabernacled among us, he is telling us that in coming to earth Jesus is the very presence of God with us. He wasn’t just some prophet. He was the very presence of God in the midst of human life.

We do not believe in a God who has stayed remote from us. Contrary to the Julie Gold/Nanci Griffith song that Cliff Richard covered, God is not simply watching us from a distance. God has traversed the distance and in Jesus he is Emmanuel, God with us. He knows what it is to live the human life with all its joys and struggles. He is not an ivory tower God.

When we struggle with suffering or injustice, Jesus has lived it. This is what he came to do. As I often say at funerals, when I go through a bad experience in life, the people who come up with the clever answers that explain my predicament are no help. They are as smug as Job’s comforters. But those who have walked the road I am on, and who come alongside me – they make a difference. So it is with Jesus.

One simple example from my life: a few years before I met Debbie, I had a broken engagement. (Or a narrow escape, as my sister called it. I married the right woman in the end!) One day, when I was particularly down, two friends of mine, Sue and Kate, rang the doorbell and said, “We’re taking you out to lunch.” What I discovered over lunch was their own histories of broken relationships.

Jesus tabernacled among us. He understands. He is still present with us by the Holy Spirit. Hear the Good News of Christmas that the Son of God tabernacled among us. He is Emmanuel, God with us.

And it’s the model for the way we spread that Good News. For after the Resurrection, Jesus told his disciples,

As the Father has sent me, so I am sending you. (John 20:21)

So the way we begin sharing the Gospel is by openly living for Christ in the midst of those who do not yet believe. We do not go on helicopter raids to bring people in, we start by going among other people, living our Christian lives before them. This is what Jesus himself, the Word made flesh, did, when he tabernacled among us. So too us.

In one town where I ministered, some Christians left the local United Reformed Church and said they were going to start a new church on a deprived estate. They hired a hall there for meetings. But did any of them move to the estate and live out their faith among the people they were supposedly going to evangelise? No.

The Word was made flesh and tabernacled among us. It is Good News for us in all that life throws at us, and it is the model for us sharing that Good News even today.

Secondly, let’s look generally at the exodus and for this we go to verse sixteen of John chapter one:

16 Out of his fullness we have all received grace in place of grace already given.

Many people say that the Old Testament is about God’s Law and the New Testament is about God’s grace. Wrong! There is grace in the Old Testament. The New Testament tells us so, in verses like this. So when Jesus comes, his mission of grace builds on what has gone before and takes it to new levels.

In Moses’ case, grace is seen in the Exodus. God sees the suffering of his people in Egypt as they are enslaved, as Pharaoh worsens their already bad working conditions, as he attempts to have male Israelite babies killed.

The Israelites themselves are not perfect, but God in his mercy and grace will save them. Moses whom he calls to lead them is also far from perfect – in fact that’s an understatement, he’s a murderer. But in grace God calls him and mercifully redirects his passions.

Grace comes before anything we ever do for God. He acted in grace to deliver the Israelites from Egypt. And when Jesus comes, he does so to bring grace on a far greater scale, a cosmic scale, even. Yes, God is still interested in setting free people who are suffering due to the sins of others, but in Jesus he comes to do even more. He comes to set people free from their own sins. He comes to bring reconciliation not only with God but with one another. And he comes to heal broken creation. For when Jesus is raised from the dead, it will be the first fruits of God’s project to make all things new, even heaven and earth, as we learn in the Book of Revelation.

If from Moses and the wilderness we learn that Jesus is Emmanuel, God with us, then from Moses and the Exodus, we learn that Jesus is – er – Jesus, the One who will save his people from their sins.

This tells us why the Word was made flesh and tabernacled among us. He came to bring this comprehensive salvation. To save us from what others do to us. To save us from what we do. To save creation from its brokenness.

Never let us reduce salvation to a personal and private forgiveness of my own sins which earns me my ticket to heaven. Yes, we do need our own sins forgiving, we do need to repent of them and put our faith in Jesus, but that is just the beginning. God saves us to involve is in the whole project of grace that Jesus heralded. We have a job to do, and Jesus is enlisting us in the ways of grace.

I love to tell the story of a keen young Christian who found himself on a train sharing a compartment with a man of the cloth dressed in a purple shirt, in other words a bishop. The young Christian had heard about these religious establishment figures and was sure the bishop would not have any vital experience of Christ, and so he said to him, ‘Bishop, are you saved?’

The bishop looked up and calmly replied, ‘Young man, do you mean have I been saved? Or do you mean am I being saved? Or do you mean will I be saved?’

Before the bemused young man could respond the bishop continued: ‘Because I have been saved – Jesus in his grace has forgiven my sins. I am being saved – Jesus by his grace is slowly making me more like him. And I will be saved – because one day there will be no more sin in this creation. I have been saved from the penalty of sin, I am being saved from the practice of sin, and I will be saved from the presence of sin.’

The bishop understood what it meant for Jesus to have given us ‘grace in place of grace already given.’

Thirdly and finally, let’s go to Mount Sinai with Moses.

17 For the law was given through Moses; grace and truth came through Jesus Christ.

Ah, the law: that’s what we associate Moses with, isn’t it? Coming down from Mount Sinai with God’s prescription of two tablets, and then all those other laws, some of which perplex us today.

So it was law in the Old Testament and grace in the New Testament after all? Except you have to remember when it was that God gave the law to Israel. It was after he had delivered them from Egypt in the Exodus and they were on their way to the Promised Land. So it’s not true that keeping God’s law was the way to salvation, it was rather how they responded to salvation.

Even so, there was a problem. Israel failed to keep the law. Prophet after prophet called them to repentance, but either they rejected the message or it didn’t stick.

Hence, the coming of Jesus with grace and truth. For grace is not just about forgiveness. It is about that on-going salvation from sin that the bishop told the earnest young Christian about.

And he does not only bring the truth, he is the truth. Jesus the truth lives among us and eventually within us by his Spirit. The truth of God is no longer laws external to us on tablets of stone. Now that truth lives within us and enables us to be different. This is the promise of Christmas. Not only God with us, not only God saving us from our sins, but God within us.

An old lady once collared me after a service and told me that what this country needed to do was simply to get back to the Ten Commandments, and then all would be well. But she missed the grace that Jesus offers here. Because on our own we fail to keep the Ten Commandments, or indeed any of God’s law. We need the grace of forgiveness, and the grace of God’s presence in our lives to transform us. If faith was just a rule-keeping exercise, Jesus would never have needed to come.

But he did come. He came to be present with us, even when we wander in a wilderness, and he calls us to do the same in the midst of others. He came to bring the greatest exodus of all, in the many ways he liberates us and this world from sin. He came to bring the inner strength we need if we are to respond to God’s love for us by being with us and within us.

If anyone has reason for joy and celebration this Christmas, it’s the disciple of Jesus. Don’t be miserable in the face of inappropriate celebrations in the world at Christmastime. Instead, show that we have greater reasons to throw a party than anybody else.

I know there are lots of things that affect our mood and our ability to celebrate at Christmas. We may have had a good or a bad year. There may be an empty seat at the table this year, or there may be new life in our family.

But in terms of our faith, the coming of Jesus gives us true strength. Christmas really is ‘good tidings of great joy.’

Exodus and the Power of Remembering

And here’s the second video I forgot to publish. This is me from last week on how the Israelites demonstrate the power of remembering (unlike Pharaoh and Egypt) as seen in Exodus 1:8-2:10

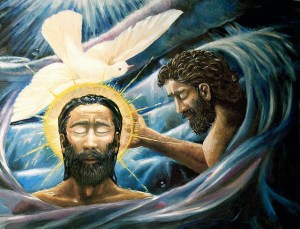

Sermon: Baptised Into Freedom (The Baptism Of Jesus)

The Advent and Christmas rush means I’ve missed posting several sermons lately. Hopefully, I’ll post them soon, even though they will be rather ‘after the event’. At least they will be present here then nearer next December for those who search this blog and others for relevant sermons.

In the meantime, here is a sermon for this coming Sunday, when we mark the baptism of Jesus.

If you follow the movies, you may have noticed that in recent months Hollywood has had a bit of a religious obsession. Much of it has been poor, or at least contentious. God’s Not Dead caricatured atheists, Left Behind took up some dubious fundamentalist theories of the end times based on a questionable series of Christian pulp fiction novels, and Noah divided opinion.

Now Ridley Scott’s Exodus: Gods And Kings has caused a stir. Not just because any such film is bound to provoke polarised opinions (and that’s just in the church!), but because Scott engaged famous white actors to play dark-skinned Egyptians so as to generate box office income. And that’s before we get to the controversies about whether the script took liberties with history and scholarship.

But Hollywood hasn’t usually worried too much about the choice between truth and a juicy story. Coming from a family where my grandmother was a friend of Gladys Aylward, I am only too aware how furious Aylward was with the fictional romance that was invented for the film about her life, The Inn Of The Sixth Happiness (never mind the dubious morals of Ingrid Bergman, who portrayed her).

Let me come back to Exodus, though. Because Mark’s account of John baptising people, including Jesus, has Exodus themes in it. I’ve said before in sermons that the Jewish people of Jesus’ day commonly regarded themselves as being in a kind of exile, even though they lived in their own Promised Land, because they were occupied by Rome. So they longed for freedom. And as well as a theme that was like the liberation from Babylon, the Gospels also contain the imagery of freedom from their original place of captivity, Egypt. The Good News that Mark is beginning to tell is couched at the beginning in Exodus language.

Our problem is that we are so used to hearing these stories in the light of more recent Christian debates and themes that we miss this. Perhaps we hear the baptism stories and start thinking about what we believe about baptism. Is it for infants, or is it for committed disciples?

But we need to return to the Exodus theme. ‘Exodus’ is a Greek word. It is usually taken to mean ‘departure’, and so the second book of the Old Testament narrates the departure from Egypt. ‘Exodus’ as a word is a compound of two other words – ‘ek’, meaning ‘out of’, and ‘hodos’, meaning ‘road’ or ‘way’. This is the road or way you take out of somewhere. It is the escape route that you follow. And so an Exodus theme is a freedom theme. It is about liberation and liberty. I want to explore the baptism of Jesus, then, and its implications for us, under this theme of ‘freedom’.

Firstly, the baptism itself. It’s implicit in Mark what is made more obvious in other Gospel writers, namely that John’s baptism is a baptism of repentance. Mark simply notes,

Confessing their sins, they were baptised by him in the River Jordan. (Verse 5b)

It’s therefore strange that Jesus embraces John’s baptism. Why does he need to repent? Again, the other Gospel writers are more explicit about this problem, but Mark characteristically keeps his account brief. Jesus certainly identifies with the people. He is the One who will lead people out of slavery – not, in this case, the slavery of Israel in Egypt, but slavery to sin. As the Israelites came through the waters of the Red Sea (or Sea of Reeds) to freedom from Egypt and her powers, so Jesus leads his people through the cleansing waters of baptism to freedom from sin.

This is the good news of Jesus’ baptism: the Messiah has come to lead his people to freedom from sin. It begins with confession and forgiveness, but it becomes a whole pilgrimage from ‘Egypt’ to the ‘Promised Land’, as that initial setting free becomes a journey in which God leads us into freedom not only from the penalty of sin but also into increasing freedom from the practice of sin, until one day, in the New Creation, we shall be free from the presence of sin.

For Jesus, that journey will embrace what our baptism service calls ‘the deep waters of death’. His Red Sea will not only be the waters of the Jordan at John’s baptism, but Calvary and a tomb. But he will rise to new life and ascend to his Promised Land, promising that we will one day go with him at our own resurrection.

This is Good News that says to us, life doesn’t always have to be like this. It doesn’t have to remain a catalogue of remorse and failure. There is hope. We do not have to hate ourselves, because God loves us to the point of offering forgiveness and new life.

Thus begins our transforming journey, in a baptism that calls us out of Egypt and on the road of increasing freedom. It’s worth reminding ourselves of this from time to time.

One person who did that in his life was Martin Luther. He was a man prone to mood swings between elation and darkness. He could be the wittiest person alive, but he could also plumb the depths. But he said that whenever he was most tempted to doubt or to give up, he would remind himself of one fact: ‘I am baptised.’

I am not saying that baptism is some religious magic trick, but I am saying that to remember our baptism is to remember the promises of God to forgive our sins, and the power of God to change us and ultimately all creation, too. It is a sacrament of hope, as well as of beginnings.

Secondly, the Holy Spirit. On the one hand, John promises,

I baptise you with water, but he will baptise you with the Holy Spirit (verse 8)

And on the other, we read,

Just as Jesus was coming up out of the water, he saw heaven being torn open and the Spirit descending on him like a dove. (Verse 10)

What does this have to do with the Exodus freedom story? It’s about the manner of God’s presence.

I’m sure you will recall that when Israel was being led through the wilderness, it was by a pillar of cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night.

But now, in the New Covenant, God’s people get an upgrade. Not only will the presence of God (cloud and fire) lead them, now that same presence will come upon all of them and dwell within them. For you frequent flyers, they have effectively gone from economy class to business class.

In Jesus’ case, there is something else. The descent of the Spirit upon him shows that he is the Messiah, for Messiah means ‘Anointed One’. He is anointed, not with the oil used to mark an earthly monarch, but with the oil of God, the Holy Spirit.

And if Jesus the Messiah is anointed with the Holy Spirit and we receive the Spirit too, then that confirms our Christian identity – we are to be ‘little Christs’. No, we are not Messiahs, and heaven deliver us from any more people in the Church with Messiah complexes, but the upgrade to the indwelling Spirit equips us for our pilgrimage to freedom. It is the witness of the Holy Spirit that confirms we are forgiven and loved. It is the work of the Holy Spirit to lead us into increasing freedom from the practice of sin, thus making us more Christ-like. (Although we may more modestly feel it’s a case of becoming less un-Christ-like!)

We need not fear the gift of the Holy Spirit. He is the Spirit of freedom. ‘Where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is liberty,’ wrote the Apostle Paul. He brings God’s freedom to us, and empowers us then to be ministers of God’s freedom in the world. Through the Spirit’s work, we offer Christ and his liberating work to those in the chains of sin – the chains of their own sin, and the chains imposed by others upon them.

And not for us the limited distribution of the Holy Spirit in the Old Covenant. Now the Spirit is given not only to a select number of God’s people, he is given to women and men, young and old, privileged and poor – anyone who desires to follow Jesus the Messiah, the leader of freedom.

Those in higher church traditions than us have a liturgical symbol for this in the way the bishop applies anointing oil (‘chrism oil’) to the foreheads of candidates for confirmation. I came to like that tradition when I used to take part in ecumenical confirmation services with Anglicans, and concluded that we were missing out on that symbolism. I can offer something ad hoc, in that I possess a bottle of anointing oil, which has a beautiful smell of frankincense, and some people find it helpful to link the fragrant aroma of the oil with the presence of the Holy Spirit, who brings freedom.

…

Thirdly, the voice of God. The terrifying thunder from the mountain on the Exodus route now becomes the voice from heaven as Jesus comes up out of the water. Heaven is ‘torn open’, the Spirit descends like a dove (verse 10), and the voice from heaven speaks:

‘You are my Son, whom I love; with you I am well pleased.’ (verse 11)

Tom Wright says[1] that we should not see the opening of heaven as like a door ajar in the sky, because heaven in the Bible is rather the dimension of God’s reality that is invisible to us. So instead, this is like an invisible curtain being pulled back so that we see the whole of life in the light of this different reality. And in this case, when heaven opens the curtain into our life, we hear the divine voice that addressed Jesus addressing us, too: ‘You are my child, whom I love; with you I am well pleased.’

And certainly that is a totally different reality in which to live. Think about God addressing Jesus this way. Mark hasn’t recorded any virtuous acts by Jesus yet at all. His baptism is his first action in this Gospel, and even that is done to him. There is not even a reference to the humility of the Incarnation in Mark. What, then, has Jesus done to earn his Father’s pleasure here? Absolutely nothing. But he hears the voice of unconditional love. God loves him and is pleased with him.

Those of you who are parents, recall those times when you went into your children’s bedrooms at night when they were fast asleep. They might have delighted you that day, or they might have been utter pickles. But still you gazed at them and whispered words about how much you loved them. You had unconditional love for them.

So ask yourself this: is God angry with me, or does he love me? Can I really believe the Good News that God delights in me? This is the liberating news of our New Testament Exodus.

And that is a transforming insight. If God loves us like this, why do we not love ourselves? I don’t mean in a self-centred way. Rather, I mean something that the author Donald Miller has recently written about. In a booklet available online called Start Life Over, he lists five principles towards changing our lives for the better. The second of these is that – strange as it may sound – we are in a relationship with ourselves, so we should make it a healthy one.

What he says is this. To some extent, we all seek the approval of others, but what we don’t notice is how we seek our own approval. It is as if we are two people: one doing the actions of daily life, the other watching those actions in judgement. Miller noticed that a friend whom he deeply admired was always doing respectful things. And he wondered: if I start doing more respectful things, will I respect myself more, and thus change for the better? He writes,

And it worked. I would find myself wanting to eat a half gallon of ice cream while watching television and I asked myself “if you skipped this, would you have a little more respect for yourself?” and the truth is I would. So I skipped it. And I had much more self respect.

I liked myself more.

This sort of thing translated into a whole host of other areas of my life. I started holding my tongue a little more and found I respected myself more when I was more thoughtful in conversation. I found myself less willing to people please because, well, people who people please aren’t as respectable, right? (Page 9)

I suggest to you that this kind of transformation is open to us when we embark on our baptismal journey of freedom, in the power of the Holy Spirit, and hear God’s voice from heaven telling us we are loved unconditionally. It makes change possible.

So often, the way we seek to promote change in ourselves and in others is through threat. We are no carrot and all stick. But all that produces is fear and paralysis. We might see some change, but it is the change wrought by sleeplessness and night terrors, rather than love. Ultimately, it doesn’t achieve much, and it affects us badly as people.

God chooses the way of unconditional love to lead us into freedom.

[1] N T Wright, Mark For Everyone, p5f.