If you ask what Methodists are known for, it might be the hymns of Charles Wesley, an expectation that we are teetotal, and regulation green cups and saucers for the compulsory tea and coffee after services and meetings. The more daring Methodists bought blue cups and saucers.

Or there might be the social side of our faith, which leads to our commitment to social action and justice.

But one area where we are less strong today is in talking about our faith to others. It’s strange, isn’t it, that a movement which began with preaching in the open air should lose its ability to speak about Jesus.

And when we don’t share Jesus, the church dies. For how else will people know about their need to follow him and be part of his family? Our actions certainly witness to him, but we then need to explain them.

We need to address this, though, not through guilt trips but encouragement. I’m aware that since I am a ‘professional Christian’, people expect me to speak about Jesus, and that may make it easier for me. However, I think this reading from John’s Gospel gives us a couple of encouragements. Both John the Baptist and Andrew, in different ways, show us a way forward. Let’s look at how they can help us.

Firstly, John talks about who Jesus is:

Everything John says is about who Jesus is. He is the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world (verse 29). This is the One who solves all our needs for forgiveness and a new beginning. Even though Jesus comes after John (which implies the listeners think Jesus is one of John’s disciples) he outranks him because he was before him (that is, John speaks of Jesus’ pre-existence) (verse 30). I came to baptise, says John, but not to draw attention to me: I wanted you to see Jesus, who is the One Israel needs (verse 31). You were used in past times to the Spirit of God alighting on certain people temporarily, but now Jesus is the One on whom the Spirit rests permanently (verses 32-33). The divine mark of approval is on him, and he will bestow the same on his disciples. He is God’s Chosen One (verse 34) – not merely a teacher or even a prophet: there is no human equal to him.

John has gathered the crowds, and his popularity has grown among the ordinary people, to the point where the religious authorities had felt the need to set up a committee to investigate and report on him. But he is not interested in his own legacy. This is not about the setting up of John The Baptist Ministries, Inc. His sole aim is to point not to himself but to Jesus. And now that Jesus is on the scene, he can back out. He really doesn’t mind when two of his own disciples respond to his testimony by leaving him to follow Jesus (verses 35-37). In fact, that’s what he wants. Job done. It’s time to wind down the operation.

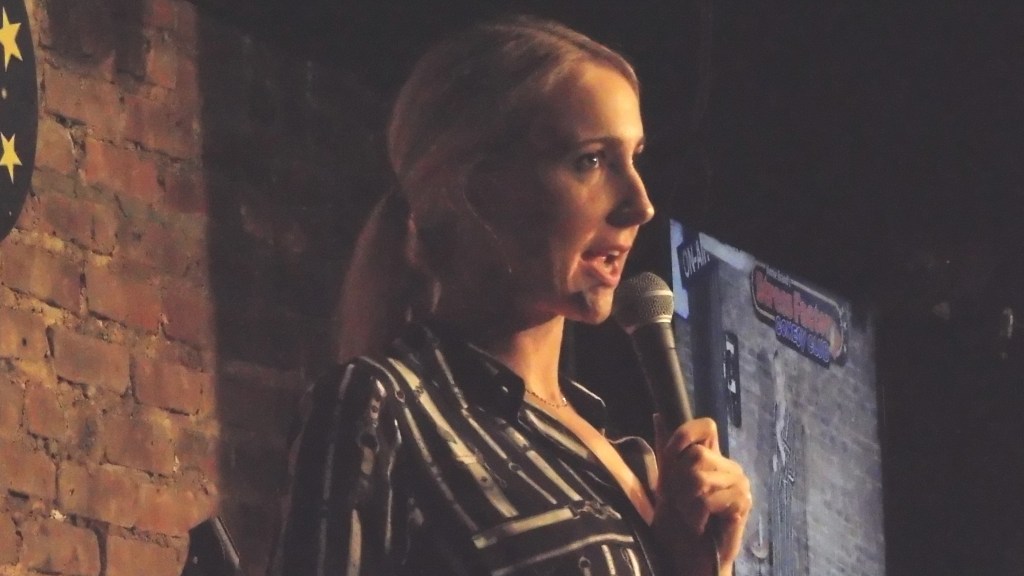

As I have been fond of saying over the years, the job of John the Baptist is to be the compère who introduces Jesus. Last weekend, Hollywood held the annual Golden Globes movie awards ceremony. A lot of the anticipatory talk in the media was about how good the jokes would be by the comedian hosting the ceremony, Nikki Glaser. But the job of the compère is not to point to themselves and enhance their reputation. It is to introduce the star of the show. That’s what John does.

And that’s our task, too. Perhaps we are grateful that it’s not about us. John reminds us to put Jesus front and centre. Maybe that’s particularly important for those of us who witness in a public and formal way, such as preachers. The late American pastor Tim Keller, who developed a remarkable ministry in what was thought to be highly secular New York City among young adults, said in his book on preaching that every time you preach you should include the Gospel. You should hold us to that. Have we focussed on Jesus? Have you heard the good news this morning? Because that’s our priority.

Most of us are not preachers, though. For us, it means that when we get an opportunity to commend Jesus to someone, we say something about who he is and how he can help them. There are so many things we can say about Jesus to people, depending on the circumstances of those with whom we are conversing. It’s not necessarily about memorising the Gospel in four easy points, although some find that helpful. It’s more what the late W E Sangster, Superintendent minister at Westminster Central Hall through World War Two, said. He spoke of the Gospel as a many-faceted diamond. We need to find the facet of the diamond that reflects Jesus the Light of the World to the people or the situation where we find ourselves.

Therefore, when we are in a conversation with someone, and we sense it would be good to say something about our hope in Jesus to help them, it pays to pause and think, what aspect of Jesus would it be most helpful for them to consider? Do they need to know about Jesus, the forgiver of sins? Would it help them to know about Jesus the healer? Or do they need to encounter Jesus who is Lord of all? Or Jesus, through Whom God made all things good? Or is it some other element of who Jesus is that would be constructive?

We could make this part of our praying for these people, too. Something like this: ‘Lord, I sense my friend needs to know about Jesus. Please show me what would be most attractive or challenging or relevant to them. And please help me to share that in an appropriate way.’

Secondly, Andrew talks about what Jesus means to him:

Andrew is possibly the most significant example of being a witness to Jesus outside of Paul and Peter in the New Testament. In fact, I once helped on an evangelistic mission where the preparatory training of local Christians was called Operation Andrew. Because Andrew is the character in the Gospels who speaks to friends and relatives and brings them to Jesus. He doesn’t preach, but he introduces people to Jesus by his personal and private conversations.

We see that for the first time in this reading:

41 The first thing Andrew did was to find his brother Simon and tell him, ‘We have found the Messiah’ (that is, the Christ).

In John 6:8-9, Andrew introduces the boy with the five loaves and two fish to Jesus, even though he doesn’t expect that small quantity to go far. But he still does it.

In John 12:20-22, some Greeks want to meet Jesus. It is Philip and Andrew who tell Jesus about them.

Andrew is that quiet, personal witness. We don’t see him preaching to the crowds, instead we see him in these private interactions that facilitate the possibility of people meeting Jesus.

And within that mode of operation, Andrew speaks about what Jesus means to him. ‘We have found the Messiah.’ Not just, ‘Jesus is the Messiah,’ but ‘We have found him.’ It’s the truth about who Jesus is, as per John the Baptist, but it’s personal. This is who Jesus is, and I’ve found it to be true in my life.

Is that not the essence of Christian witness for most of us? We have discovered that the claims of Jesus are true, but not merely in theory: we have found them to be true in our own lives. That gives us something we can share with others, not by preaching, but in the to-and-fro of respectful conversation.

Again, it is not about bigging up ourselves, it is about promoting Jesus. He is the focus. Many of us will not have dramatic stories to tell, but we shall have that knowledge that Jesus has been at work in our lives, and we can share that. Others of us may have known times when Jesus did indeed work in a remarkable way in our lives, but when we tell it, we don’t emphasise all the gory stuff about ourselves: rather, we put the emphasis on what Jesus did.

Therefore, whether or not we have had the sort of life that can get written up as a dramatic religious paperback, every Christian can reflect on their lives and think of the times when they have known for sure that Jesus was at work by his Spirit, and we can bring that into conversation when the time is right. It won’t be by making a formal, prepared speech, it will be in the way that friends and family tell each other stories about their lives. We do that, and then we let the Holy Spirit do the work of making this real to the people with whom we share. We pray, of course, for the Spirit to do that.

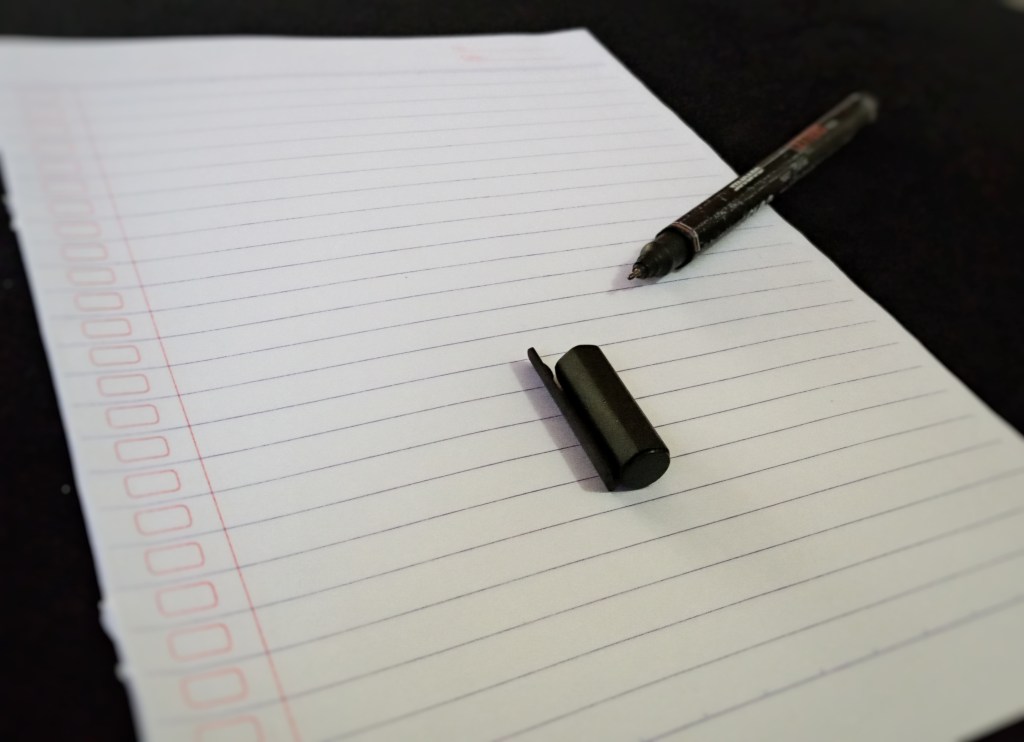

At this point, if this were a seminar rather than a sermon in a church service, I would want you to take a pen and paper, and spend some time thinking over the story of your own life, then writing down those occasions when you have known that Jesus did something particular for you.

But since we are not in a seminar environment, I want to suggest that you find half an hour for yourself at home to try that very exercise. Recall and write down the times when Jesus has done something special in your life. And when you have done that, I want you to work on memorising it. Not necessarily in a word-for-word way, because if you just regurgitate that to others, you will sound stilted and unnatural. In fact, they will feel like they are being preached at, and not in a good way.

One approach that some find helpful is to turn that story of Jesus’ work in you into a series of short bullet points that you can remember. What are the essential parts of the story?

What I have in mind here is, I think, in harmony with something the Apostle Peter said in his First Epistle. Writing to a group of Christians who were fearful of a negative response to their faith that would have been far worse than anything we might face, he said this:

But in your hearts revere Christ as Lord. Always be prepared to give an answer to everyone who asks you to give the reason for the hope that you have. But do this with gentleness and respect (1 Peter 3:15).

This is a way in which we can have a reason for our hope: by recounting the ways in which Jesus has shown his faithful love to us over the years. I am sure that if I asked you, Christian-to-Christian, whether Jesus has been good to you over the years, you would probably say ‘Yes.’ What comes to your mind is helpful in witness, too. We can avoid flowery, churchy language, and share with people in a simple way what Jesus has done for us.

Conclusion

Let’s go from here and conduct an experiment. Let us meditate on the many things that are true about Jesus, so that we can offer an aspect of him in conversation with others.

And let’s reflect on our own experiences with Jesus, so that we are ready to share them when the Spirit prompts us that to do so would be helpful.

May it be that the Holy Spirit encourages us through this to speak about our faith as well as demonstrate it.