When David Cameron was Prime Minister, there was a big public debate about ‘British Values.’ Some very conservative Muslims had been accused of undue influence in Birmingham schools to promote militant Islam. Mr Cameron said that anyone living in the UK should abide by ‘British Values’, by which he meant things like democracy, the rule of law, personal and social responsibility, freedom, and tolerance of other beliefs. He cited things like the Magna Carta – although that was a little awkward, as the Magna Carta was an English, not a British document.

Whatever you think of that debate, it shows the reasonable assumption that a nation, a society, or a culture has certain shared values. We may argue about what they are, but the basic idea is sound.

That means, when we come to the Bible, that it is helpful to know about the values of the culture in which a story is placed. Doing that this week with the story of Jesus’ baptism has helped me see it in a new light. The culture into which Jesus was born was

A traditional Mediterranean culture where society stressed honour and shame[1].

Middle Eastern societies have reflected those values of honour and shame right up to modern times. My late father spent a couple of years in Arab countries when he was in the RAF, and I remember him telling me that no matter how much one might disagree with someone from that region, one should never shame them: that was a terrible insult. You should always treat them with dignity and never shame them.

Today, I want us to read about the baptism of Jesus through the lens of honour and shame. It is something we can do throughout the Bible with great profit[2], but today we shall just think about Jesus’ baptism in this way.

Firstly, we’re going to consider shame:

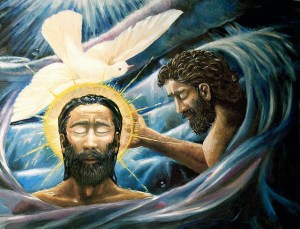

13 Then Jesus came from Galilee to the Jordan to be baptised by John. 14 But John tried to deter him, saying, ‘I need to be baptised by you, and do you come to me?’

15 Jesus replied, ‘Let it be so now; it is proper for us to do this to fulfil all righteousness.’ Then John consented.

John knows that Jesus is superior to him. Immediately before this, he has been prophesying the coming of Jesus, saying that Jesus is more powerful than him, and that he is not fit to untie Jesus’ sandals (verses 11-12). Whether he fully understands Jesus’ divine status at this point we don’t know, and whether he knows Jesus is sinless we also don’t know, but he does recognise that he is outranked by Jesus. Therefore, he says, he should honour Jesus, not the other way round.

But Jesus does not pull that rank. He takes a place below John by submitting to his baptism. He takes the place of humility, but more than that, he takes the place of humiliation, of shame. Baptism was for those who were ashamed of their sins, and Jesus identifies with the shamed.

Of course, this is a foreshadowing of the Cross, the deepest example of Jesus identifying with the shamed, when he suffered one of the cruellest forms of execution ever devised. But for now, notice that Jesus puts himself alongside the shamed. He could pull rank, but he doesn’t. No wonder the tax collectors and ‘sinners’ loved him.

Shame takes many forms. In part, it is the shame we experience for our sins, if we have any moral compass. Here, by identifying with those who are ashamed of their sins, we see the Jesus who will pronounce divine forgiveness to some of the most outrageous of sinners, those who commit some of the most socially unacceptable sins.

It’s been my privilege on occasion to assure people who have secretly carried the guilt of awful sins that they were too ashamed to admit publicly that God in Christ forgives them. I have seen a burden disappear from someone’s face. And it is all made possible by the Jesus who identifies at his baptism and later at the Cross with those shamed by sin, and who in between those two episodes spends time befriending such people.

But there is more to shame than this. Some people have shamed foisted onto them. These people are not so much those who have sinned, but those who have been sinned against. Somebody else has done something dreadful to them, and they have been told they must keep it secret, or there will be terrible consequences for them. Sometimes, the perpetrator engages in what we call today ‘gaslighting’, where they manipulate their victim to the point of them doubting reality. This is incredibly damaging to someone’s self-esteem. I’m sure I don’t need to elaborate too much.

When Jesus identifies with the shamed, I believe he identifies with these people, too. Jesus is for those who have been sinned against. He has love, compassion, acceptance, and healing for people who have endured such trauma.

The Christian Church is called by Jesus also to identify with the shamed, whether that shame is caused by sin, being sinned against, or some other cause. It is our calling today to bring the love and healing of Jesus to those carrying shame.

It includes prayer as well as action. In Daniel chapter 9 verses 1 to 19, Daniel confesses the sins of his people that led to the Exile in Babylon, even though he personally was not responsible. He identifies with the shamed.

One of the problems Jesus had with many of the Pharisees was that they did not do this. Instead, they made it very clear that they distinguished themselves from the shamed. In Luke 18:9-14 Jesus tells the famous Parable of the Pharisee and the Tax Collector, where the Pharisee begins his prayer with the ominous words, ‘God, I thank you that I am not like other people’ (verse 11). It is so easy for us to fall into that trap, too. We don’t want to be tarred with the same brush as others whose actions are wrong. But Jesus tells us to resist that. Let us come alongside the shamed with the love of God in Christ, rather than setting ourselves up as being above them.

Secondly, we move from shame to honour:

16 As soon as Jesus was baptised, he went up out of the water. At that moment heaven was opened, and he saw the Spirit of God descending like a dove and alighting on him. 17 And a voice from heaven said, ‘This is my Son, whom I love; with him I am well pleased.’

Well, can you get a better way of being affirmed or honoured than that? Already, John the Baptist – a prophet – has honoured Jesus. Now heaven speaks, and quotes Scripture in doing so. A prophet, Scripture, and the direct voice of God. Top that if you can.

But why is Jesus being honoured like this at this time? There is more than one way of looking at this.

One is to say that God is honouring Jesus for what he has just done in humbling himself to identify with the shamed at his baptism. God is pleased that Jesus has given a preview of his mission. God honours the way Jesus humbles himself, or ‘made himself nothing’, as Paul was to describe it in Philippians 2. This is God setting his seal of approval on the way in which Jesus will conduct his ministry. When Muslims deny the suffering of Jesus because that would supposedly be beneath the dignity of a prophet, let alone God, we say no: this is the glory of God, that there is no depth too low that Jesus will not stoop to bring salvation.

Another way of looking at the Father honouring Jesus here is to say that this happens just before Jesus’ ministry begins. He will go from here into the wilderness and then he will start his mission. On this reading, God is unconditionally affirming Jesus. If we take this approach, then Jesus goes into the difficult conflict in the wilderness and then into all the challenges of his mission having heard the ringing endorsement of the Father, who had underlined his status (‘This is my Son’) and that he loves him. This could be important too, because if you are going to face difficulty as Jesus was, then what could be better for helping your resilience and perseverance than remembering that you are God’s Son and you are loved?

Is that not something we need, too? Yes, Jesus was the Son of God in a unique way, but we are also children of God in a different way – we are adopted[3] – but nevertheless we have incredible privilege as a result. And we are loved. We are not earning God’s love. It is already there for us to accept and receive.

If we put these two approaches together, we get an application for us. We remember that – as in the words of John – ‘We loved because he first loved us.’ Anything and everything we do as Christians is a response to God’s love for us in Jesus. He loved us first. We only go into our discipleship as those who are already loved, already affirmed, already honoured with that love. We are honoured too by the fact that God has adopted us as children into his family, bearing his name – Christians, little Christs. This is our foundation. We bear the honour of God.

Yet that calling we have, and which we take up bearing the honour of God, is to bear the shame of the world. It is to live humbly among the shamed, witnessing to God’s great love for them, too. We have the strength to do this, not only because God gives us the Holy Spirit but also because he has honoured us with his love and adoption of us.

And further, following this calling to live the love of God among the shame, will rarely earn us the adulation of the world. It will more likely earn us the reproach – and yes, the shaming – of the world, for bringing dignity, belonging, love – and yes, honour – to those who are despised by the world.

Conclusion

We began by talking about the values that different societies have. We have seen that the ways of Jesus challenged the values of his culture. Our society is not the same: it might be that we have more sympathy for those who have been shamed, at least when it has been inflicted upon them.

But even so, if we live out the baptised life of Jesus, identifying with the shamed and sharing God’s love with them because we have been honoured with receiving the love of God ourselves, that will still be a challenge to our world. Some will like it, others will not.

However, as adopted members of Jesus’ family, it is incumbent upon us to follow this calling, when it finds favour with others and when it doesn’t.

May God give us such a deep experience of his love through the Holy Spirit within us that we have the fortitude to do so.

[1] Craig S Keener, The Gospel of Matthew: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary, p131.

[2] See Judith Rossall, Forbidden Fruit and Fig Leaves: Reading the Bible with the shamed.

[3] See Rossall, pp 127-135.